Found 55 talks archived in Planetary systems

Abstract

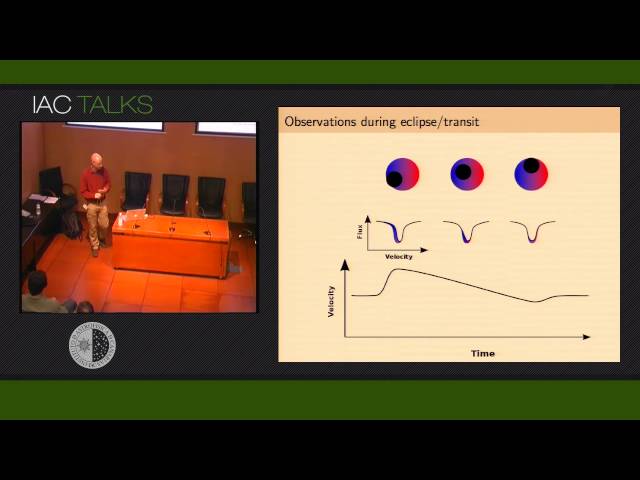

Spectroscopic observations of stars do not only provide us with valuable information about the stars themselves, but over the last years such observations have lead to numerous exoplanet discoveries and new insights into planet formation. One important clue emerged at the dawn of the field: the existence of hot Jupiters, gas giants with orbital distances much smaller than an astronomical unit. We and other groups found some of these planets orbiting their stars on highly inclined or even retrograde orbits. I show how the orientation of the stellar axis in relation to the orbital plane (obliquity) reveals the mechanism by which these planets move inwards. Similar measurements in multiple transiting planet systems, with smaller planets will further enhance our understanding of the formation and evolution of planetary systems. In order to take those measurements we need to improve the way we analyze spectra. I present recent results obtained with such a new technique. These include multiple planet systems and results from my "BANANA" survey of close binaries, some of which, such as DI Herculis, also show strong misalignment. The same technique will allow for a reduction of stellar noise in radial velocity surveys, improving our ability to search for smaller, more Earth like planets around bright nearby stars.

Abstract

Ultracool dwarfs represent the low-mass tail of the distribution of primary masses for which planets can be found with the Kepler satellite. Our team has identified 42 new ultracool dwarfs in the Kepler field of view that have started to be observed with this space telescope via its General Observer and Director Discretionary Time programs. First results of a study of Kepler light curves of 18 very low-mass dwarfs will be presented at this talk. It is demostrated that Kepler is sensitive to moon sized companions of ultracool dwarfs at short orbital periods (few days), and an intriguing candidate will be shown. Results from a ground-based infrared transit survey will also be presented which confirm the lack of Hot Jupiters around very low-mass primaries. Last but not least, a concept for a sustainable hybrid Hypertelescope that would be crucial to follow-up rocky planets will also be introduced.

Abstract

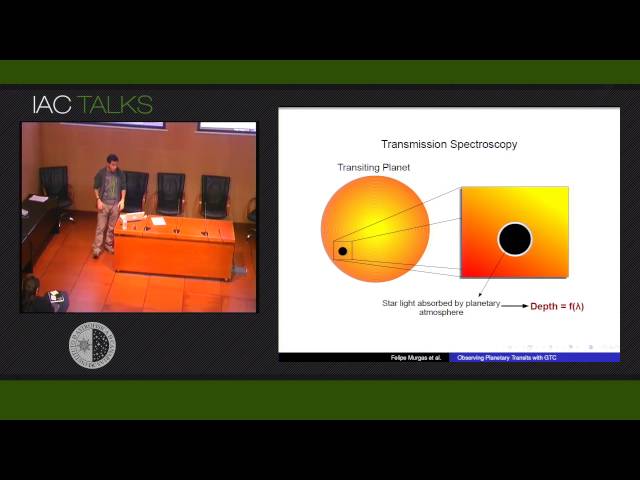

So far more than 800 planets have been discovered and their

characterization is becoming more important. Transiting planets offer

the unique opportunity of detecting planetary atmospheres, helping to

improve the theoretical models of atmospheric composition under

different physical parameters (densities, irradiation, etc). However,

the precision needed to detect atoms and molecules, requires big

telescopes and stable instruments in order to obtain a good

signal-to-noise. In this talk I'll review the efforts, technical

challenges and current results that our group of Planets and Low Mass

stars is obtaining using GTC to study extra-solar planets.

Abstract

Traditionally, astronomers study stars and planets by telescope. But we can also learn about them by using a microscope – through studying meteorites. From meteorites, we can learn about the processes and materials that shaped the Solar System and our planet. Tiny grains within meteorites have come from other stars, giving information about the stellar neighbourhood in which the Sun was born.

Meteorites are fragments of ancient material, natural objects that survive their fall to Earth from space. Some are metallic, but most are made of stone. They are the oldest objects that we have for study. Almost all meteorites are fragments from asteroids, and were formed at the birth of the Solar System, approximately 4570 million years ago. They show a compositional variation that spans a whole range of planetary materials, from completely unmelted and unfractionated stony chondrites to highly fractionated and differentiated iron meteorites. Meteorites, and components within them, carry records of all stages of Solar System history. There are also meteorites from the Moon and from Mars that give us insights to how these bodies have formed and evolved.

In her lecture, Monica will describe how the microscope is another tool that can be employed to trace stellar and planetary processes.

INFN, Napoli, Italy

Abstract

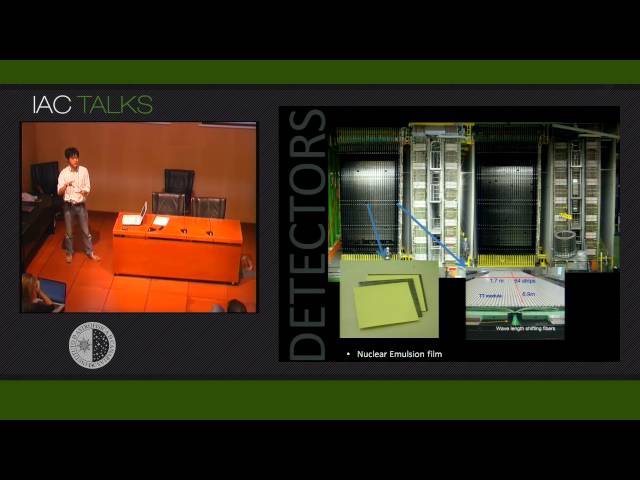

The origin and structure of the Earth's crust is still a major question. Current measurements of the nearby crust are based largely on seismic, gravimetric and electrical techniques. In this talk, we introduce a novel method based on cosmic-ray muons to create a direct snapshot of the density profile within a volcano (and/or other geological features). By measuring the muon

absorption along the different paths through an object (volcano, mountain, a fault, ...), one can deduce the density profile within the object. The major feature of this

technique makes possible for us to perform a tomographic measurement by placing two or more cosmic ray detection

systems around the object. Another strong point of this technique is the possibility to carry out fulltime monitoring, since muons are incessantly arriving, recalling they are

the most numerous energetic charged particles at sea level.

Abstract

For the first time, we present the low-mass function of the entire young star cluster Sigma Orionis (3 Myr, 352 pc, no internal extinction) from 0.25 Msun through the brown dwarf regime down to 3-4 Mjup in the planetary-mass domain. We have used VISTA Orion data (ZYJHKs) in the magnitude interval J= 13 - 21 mag (completeness at J = 21.0 mag, Z = 22.6 mag, and 10 Mjup). Combined with Spitzer/IRAC (3.6 and 4.5 micron) and optical images (Iz-band) from our archives has allowed us to identify over 200 cluster low-mass member candidates in an area of 0.79 deg2, i.e., uncovering most of the cluster area. All of these objects have colors compatible with spectral types M, L, and T, i.e., Teff = 3000-1000 K. 23 of them are new planetary mass candidates in the Sigma Orionis cluster, thus doubling the number of cluster planetary mass objects known so far. By considering the Mayrit catalog, we have "extended" our mass function from 0.25 Msun up to the high-mass stars (O-type) of the cluster, covering four orders of magnitude in mass.

Abstract

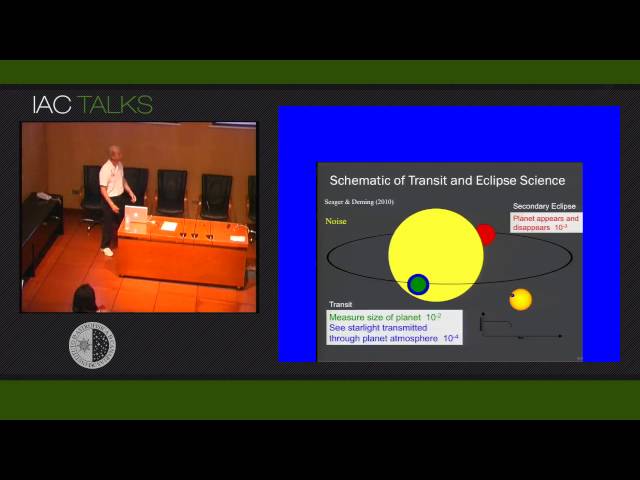

We review observations of a representative set of extrasolar planets that transit their stars, concentrating on those discovered and characterized by the XO Project. Spectra of these planets in transit and in eclipse have made significant contributions to our understanding of hot gas giant exoplanets, including 1) evidence for planet-planet scattering to transfer the planets from where they are formed to where we observe them, 2) hot stratospheres of these exoplanets, and two possible mechanisms to maintain them, and 3) water vapor detected in the near-IR spectrum of the exoplanet XO-1b in transit. For the latter case, we compare near-IR spectra obtained with two HST instruments: NICMOS and WFC3 with its new spatial scanning technique. We then present the spectrum of the super-Earth exoplanet GJ 1214b from the visible to the infrared, and focus on the definitive results obtained with HST WFC3 that show a featureless near-IR spectrum, indicative of either a large mean molecular weight in the planet's atmosphere, or obscuring haze (Berta et al. 2012). We identify similar observations that are being made with HST now, and will be made with JWST, and other telescopes in the future. We conclude by summarizing the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, TESS, which will discover the nearest, transiting rocky exoplanets, those most interesting and most suitable for follow-up characterization of the sort we have presented.

Abstract

At the end of 2008, on ideas of teams from the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur (OCA) and IAC, the CoRoT satellite observed the star HD 46375, known to host a non-transiting Saturn-mass exoplanet with a 3.023 day period. HD 46375 is the brightest star with a known close-in planet in the CoRoT accessible field of view. As such, it was targeted by the CoRoT additional program and observed in a CCD normally dedicated to the asteroseismology program, to obtain an ultra-precise photometric lightcurve and detect or place upper limits on the brightness of the planet. In addition, a ground-based support was simultaneously performed with the high-resolution NARVAL spectro-polarimeter to constrain the stellar atmospheric and magnetic properties. In this seminar, I will present the main results, in particular the stellar constrain we obtained thanks to the detection of the oscillation mode signature and the plausible detection of the planetary signal, which, if confirmed with future observations, would be the first detection of phase changes in the visible for a non-transiting planet.

Abstract

This question is important because a large fraction of planetary nebulae (about 80%) are bipolar or elliptical rather than spherically symmetric. Modern theories invoke magnetic fields, among other causes, to explain the rich variety of aspherical components observed in PNe, as ejected matter is trapped along magnetic field lines. But, until recently, this idea was mostly a theoretical claim. Jordan et al. (2005) report the detection of kG magnetic fields in the central star of two non-spherical PNe, namely NGC1360 and LSS1362. We find that, contrary to that work, the magnetic field is null within errors for both stars. Then, a direct evidence of magnetic fields on the central stars of PNe is still missing — either the magnetic field is much weaker (< 600 G) than previously reported, or more complex (thus leading to cancellations), or both. The role of magnetic fields shaping PNe is still an open question.

Abstract

I present a general overview of the PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars (PLATO) space mission. PLATO was approved by ESA’s Science Programme Committee, together with Euclid and Solar Orbiter missions, to enter the so-called definition phase, i.e. the step required before the final decision is taken (only two missions will be implemented). To be launched in 2018, PLATO is a third generation mission, which will take advantage of the scientific return from the currently flying space missions CoRoT (CNES, ESA, launched in 2006), and Kepler (NASA, launched in 2009). Moreover, the preparation and exploitation of the missions will benefit from the GAIA (ESA) mission data, together with new generation ground-based instrumentation like North-HARPS, GIANO, CARMENES, etc. Finally, I summarize the current organization status of the mission,focusing on the Spanish role within the consortium.

Upcoming talks

- Quantum Simulators for the Cosmos: From Confining Strings to the Early UniverseDr. Enrique Rico OrtegaThursday December 4, 2025 - 10:30 GMT (GTC)

- Colloquium by Junbo ZhangDr. Junbo ZhangThursday December 11, 2025 - 10:30 GMT (Aula)